The NCAA’s investigation into one of the worst academic scandals in the history of college sports collapsed Friday with the NCAA ruling that it will not punish the University of North Carolina’s athletic department for “paper courses” taken by thousands of students, many of them athletes, over a period of close to 20 years.

The Committee on Infractions concluded in a 26-page decision that the lenient classes in the school’s African and Afro-American studies classes, that never met, rarely involved university faculty and often provided passing grades in exchange for one short paper, were also taken by regular students and the NCAA could not prove the classes constituted an unfair benefit for UNC athletes.

The panel did find two violations in the case, a former department chair and a former curriculum secretary failed to cooperate during the investigation.

Members of the Committee on Infractions who reviewed this case are Carol Cartwright, president emeritus at Kent State and Bowling Green; Alberto Gonzales, dean of the law school at Belmont and former attorney general of the United States; Eleanor W. Myers, associate professor of law emerita and former faculty athletics representative at Temple; Joseph D. Novak, former head football coach at Northern Illinois; and Jill Pilgrim, an attorney in private practice.

Given the fact North Carolina could have faced severe penalties, including loss of two national championships in 2005 and 2009, the ruling was a huge victory for North Carolina, and another unintended public relations disaster for the NCAA.

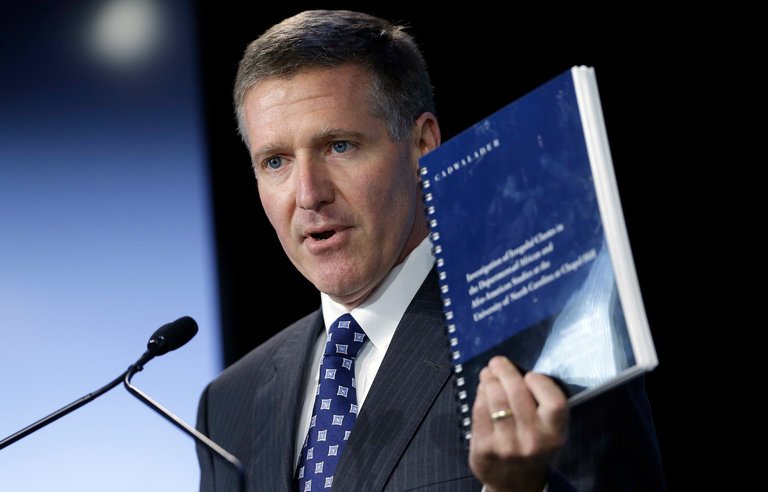

SEC commissioner Greg Sankey, the head of the Committee on Infractions, was troubled by North Carolina’s shifting positions about whether academic fraud occurred” but said the panel “couldn’t conclude violations’’ and was powerless to act because of the rules set up by its membership that also for individual schools to determine whether academic fraud occurred on their campuses.

North Carolina said the work was assigned, completed, turned in and graded, often by the former secretary, under the professor’s guidelines. While the university admitted the courses failed to meet its own expectations and standards, the university maintained that the courses did not violate its policies at the time.

Newspaper reports in the state of North Carolina claim there were 3,100 questionable classes, many of them so-called reading classes in which little or no work was done. Half the students enrolled were athletes and the program went on for between 17, 18 years.

They were mostly administered by a staffer Deborah Crowder and many of the students were recommended by athletic academic advisors. It was considered so serious the university’s accreditation board briefly placed the school on probation. Along the way, a chancellor was fired, a whistle blower was fired and a history teacher was temporarily stopped from teaching a course on big time athletics.

The panel did not conclude, based on the record before it, that extra benefits were provided to student-athletes. The panel noted the former secretary credibly explained during the hearing that she treated all students the same. “While student-athletes likely benefited from the courses, so did the general student body,” said Sankey. “Additionally, the record did not establish that the university created and offered the courses as part of a systemic effort to benefit only student-athletes.”

The panel reviewed whether the former counselor, who also served as an instructor while employed at the university, acted unethically and provided academic extra benefits to women’s basketball student-athletes. The panel found the record did not discredit the former counselor’s statements at the hearing regarding a consistent level of assistance to all students. As a result, the panel could not conclude that she provided women’s basketball student-athletes with extra benefits or acted unethically.

The allegations also included a charge that North Carolina failed to monitor and demonstrate appropriate controls with respect to the courses and the former counselor. In reaching its conclusions, the panel said the limitations in the record required it to, at best, infer motives based on the large number of student-athletes who took the courses and received high grades. The panel concluded that while student-athletes and athletics programs may have benefitted from utilizing the courses, the general student body also benefitted. Based on both the information available in the record and North Carolina’s support of the courses that were offered as not violating its policies, the panel could not conclude that the university failed to monitor or lacked control over its athletics program.

The North Carolina case is history.

But if the NCAA wants to regain its moral authority in higher education in the future it needs to push its members to make some long-needed rules changes so the loop holes can be closed and other schools can’t follow the same game plan to keep academics from becoming a farce.

Search

Tags

Featured On

Recent Posts

Archives

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- October 2013